#WeAreNot9to5 is a campaign to share a series of lived experience stories about mental health and substance use from our Not 9 to 5 community. Our aim is to encourage us to learn from one another.

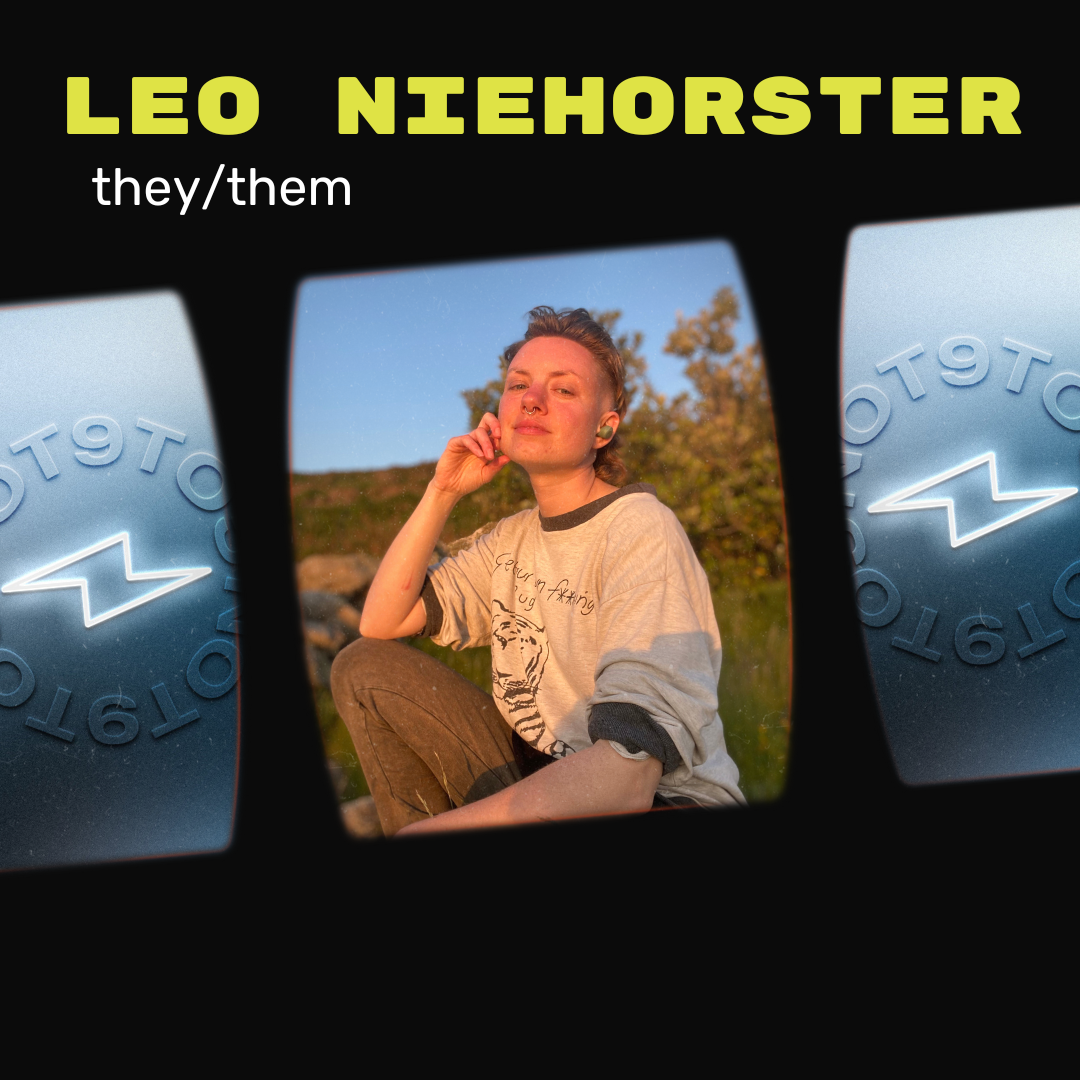

This story written by chef Leo Niehorster is about being queer in professional kitchens:

Restaurant kitchens are not set up for people like me. While researching my next kitchen job and checking out the Instagram pages of all the famous fine dining restaurants I was excited about, I didn’t see one person who looked like me. In fact, they all looked very similar – they were all white men. I’ve always found it hard to imagine myself doing something until I saw people I related to doing it. Despite enjoying cooking my whole life and searching for a profession where I could express my creativity, being a chef always felt off the table. I didn’t think it was an environment I belonged in due to the lack of representation and the stress/aggression that was portrayed on TV. I tentatively started cooking professionally at 31, getting a taste for it and gaining some confidence in the cafe at my local climbing gym. When I started it last year, I was already 15 years behind and a different generation to everyone getting their Professional Cooking Diploma.

I’m relieved I didn’t grow up in this industry. When I was younger, vulnerable and impressionable, I would have internalised and accepted how this industry treats people. It turned out that when I progressed from the relaxed, protected environment of the climbing gym kitchen to an actual restaurant with awards, the culture was more like a Gordon Ramsey TV show than I’d feared. Toxic masculinity fuelled a culture of competitiveness, ego, toughness, overwork, and aggression. I’ve had conversations with chefs who are proud of working 80 and 90 hour weeks, as if they deserve an award for martyring themselves. Since the working conditions are normalised, those who question it or struggle with it are seen as people who don’t belong in hospitality. They are seen as not caring enough or not being tough enough for this life.

This is where being queer has granted me an advantage. I understand that queers live outside ‘the system.’ We have always had to find our own ways of doing things in a way that works for us – we don’t accept the status quo. Just because things are normalised, does not mean we have to accept them and it doesn’t mean they’re right.

The kitchen reached 37.5 degrees celsius the other day with the pot wash area a few degrees hotter. I really struggled, feeling exhausted and overwhelmed by the heat. I tried to talk to my colleagues who’d been working in kitchens most of their lives about how we can make the heat easier to tolerate and was told “that’s just how it is, you need to get on with it.” Chefs have created a narrative of toughness around being able to endure the conditions in the kitchen.

Anthony Bourdain is quoted as saying “There are two kinds of people in this world. There are people who like the relentless futility, heat, pressure, the madness, the insanity of restaurant kitchens. Then there’s everybody else: normal people.” In some ways I understand this perspective and what feels like a judgement against the “normal people”: some nights when we are really busy, it’s really hot or something goes wrong, I end the night pumped with adrenaline and feeling like I’ve won a war. But that creates a divisive, hierarchical us-versus-them mentality with us as the chefs who have triumphed against the demands of the public and front of house staff.

Bourdain is also alluding to the exclusivity and inaccessibility of restaurant kitchens: one of the many problems with this culture of toughness is that only a very specific kind of person can survive it. This is why the culinary industry is still mostly made up of the aggressive, confident white men who created this culture.

April Lily Partridge, sous chef of The Ledbury in London, is the second woman to ever win the Roux Scholarship and has recently won Chef to Watch at the National Restaurant Awards. In a recent interview she talked about experiencing anxiety and said “As a woman in this industry, I have to be strong… I have to put in that extra 10% or I will be walked over.” What if we didn’t have to be strong or measure ourselves against this toughness? What if we could just be ourselves and still be taken seriously and respected?

There’s a famous phrase used to talk about restaurant kitchens: “If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen.” This is a phrase I’ve come to hate as I think it gaslights employees in to feeling like it’s their fault they’re struggling and that they just need to toughen up. I’d like to turn the phrase around and tell head chefs that if they can’t stand the heat, they should get out of the kitchen. Head chefs are usually the ones who end up shouting at their employees because they can’t handle the pressure they are under, expecting employees to bear the burden of their stress. When in fact, head chefs would find it much easier to “handle the heat” if they honed traditionally perceived feminine skills like collaboration, communication and teamwork with front of house staff and the other chefs.

The ability to regulate your emotions is hugely important in a fast paced environment when under pressure yet emotional intelligence isn’t valued in our patriarchal society.

As the industry currently is, this job is physically and mentally exhausting and we need to take care of ourselves outside work in order to recover. Men typically aren’t taught how to look after themselves while not in work: self care is seen as “feminine” and men who look after themselves are sometimes made fun of, or even put in danger by men upholding toxic masculinity. They often turn to unhealthy coping mechanisms, like alcohol, to avoid their problems and end up bringing their stress back to work with them the next day.

The ray of hope is that women and marginalised people who don’t fit in to straight white male kitchens are finding their own ways of cooking professionally thanks to social media and the diversity of food businesses which there are now spaces for in our society. We’re creating thriving Instagram cooking pages, food stalls, supper clubs and being personal chefs or retreat chefs. But this means we often need to work independently before we’re ready. There are many culinary techniques, especially knife skills, that I’ve learned from more experienced chefs who have taught me on the job. Without getting to work in established kitchens with experienced chefs, we miss out on many learning opportunities which we deserve. Working independently, we also miss out on the camaraderie and community created by working together in a fast paced environment which requires teams to pull together.

There is also the argument that queer and marginalised people shouldn’t aim to assimilate in to the colonial, sexist institution of fine dining. We should instead aim for liberation outside the framework and value system of this world. And we are: many independent, more casual food places with a focus on community, sustainability and supporting marginalised people are springing up all over the world.

These places care as much and are just as creative with their food as traditional fine dining restaurants, but don’t rely on the discriminatory, Eurocentric standards or ways of working. I believe that these food places are the future of the culinary industry.

To learn more about Leo Niehorster and their experiences working in the UK hospitality industry, visit them on Instagram.